Germany’s Climate Policy — Challenges and Milestones

© DWIH Tokyo/iStock.com/acinquantadue

© DWIH Tokyo/iStock.com/acinquantadue

December 23, 2020

[by Toru Kumagai]

Germany is one of the most ambitious countries in the world in its effort to reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gas emissions. The Merkel administration enacted the Klimaschutzgesetz (Climate Protection Law) on December 18, 2019, making the country the first in the world to mandate by law that its CO2 emissions targets should be achieved. Nevertheless, the transition towards a decarbonised economy will not go smoothly.

Aiming to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050

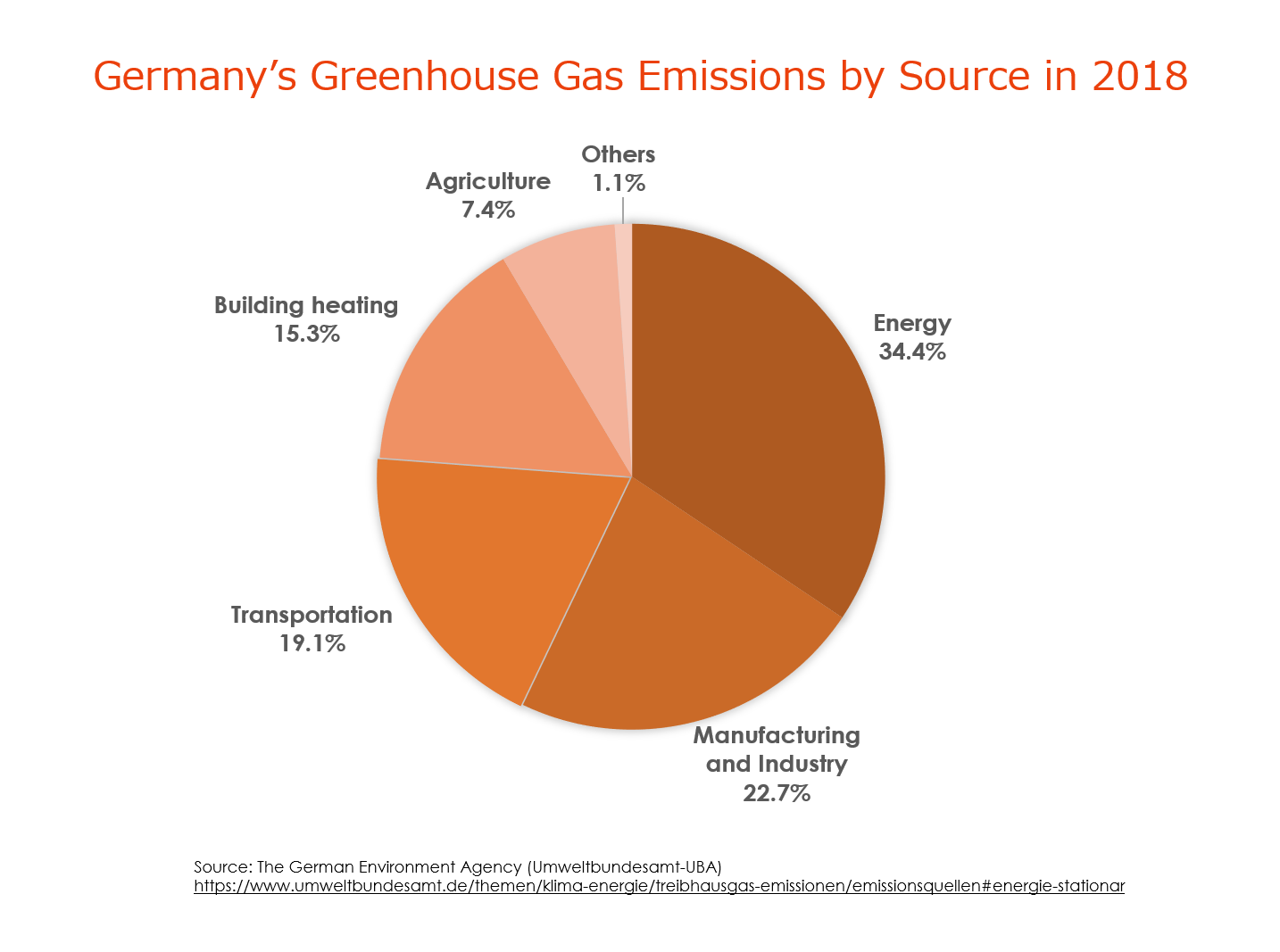

Under the law, the federal government sets reduction targets for the energy, transportation, building heating, and other sectors, and requires the ministers of the relevant ministries and agencies to review their progress annually. The Minister of Economic Affairs, for example, is held responsible for reducing greenhouse gas emissions from the energy sector; the Minister of Transport for emissions from vehicles and other means of transportation; and the Minister of Agriculture for emissions from farming.

Specifically, the German government has set a goal of reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55 percent by 2030 compared with 1990, netting out to zero by 2050.

Expected to fall short of 2020 climate goals

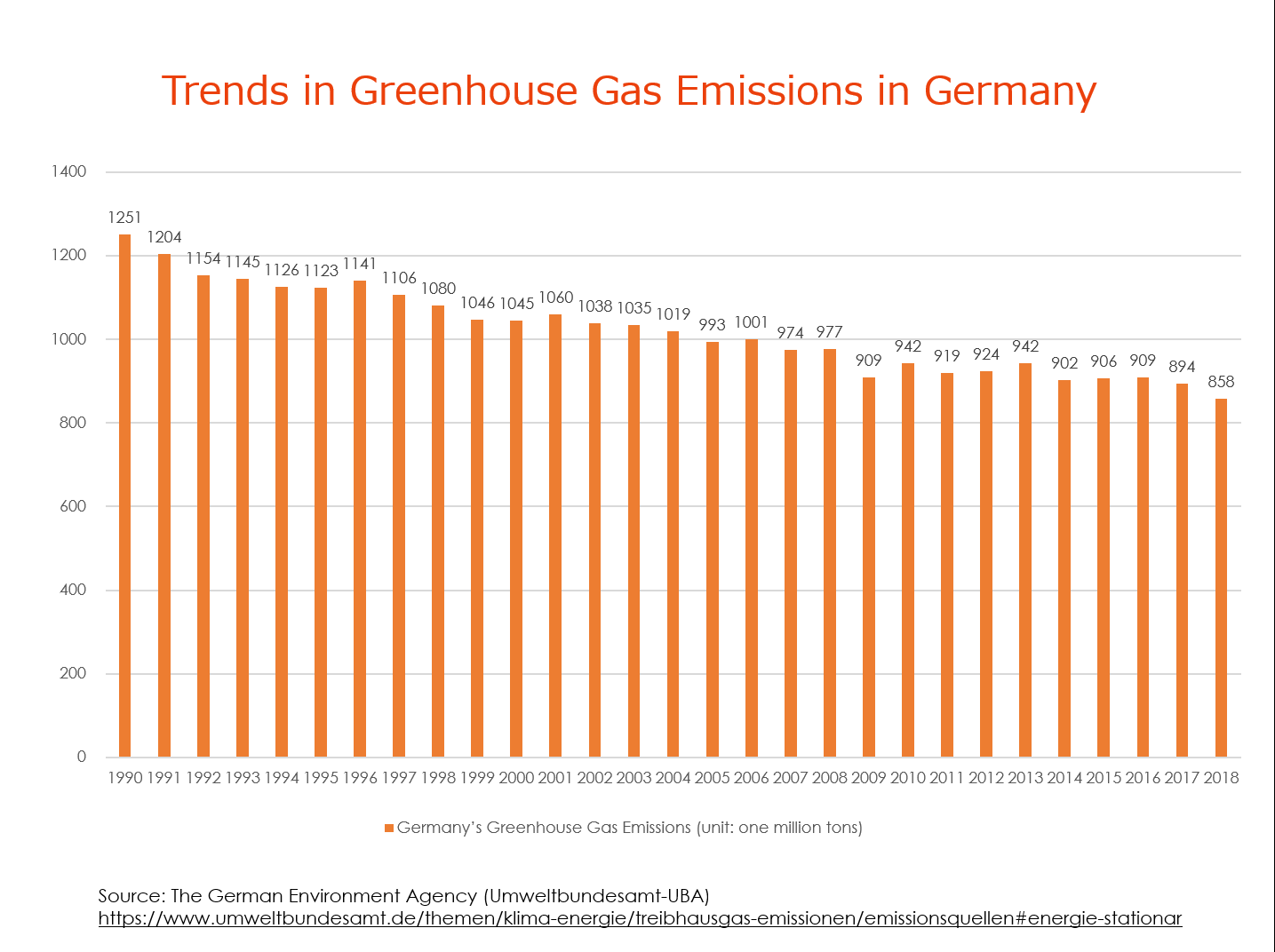

According to the 2019 climate protection report published in August 2020, Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2018 amounted to 858 million tons, which represents a 31.4 percent cut compared to 1990.

The Merkel administration initially set a target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent from 1990 by the end of 2020. The report indicates, however, that the amount of emissions at the end of 2020 is only expected to be reduced by about 36 percent below 1990 levels, failing to meet the goal of a 40 percent reduction.

This is because the reductions in the transportation and building heating sectors are falling behind schedule. Efforts to reduce emissions in the energy industry however – including electricity and gas – have made good progress.

The climate protection report is apprehensive particularly of the transportation sector, as the emissions from means of transport account for about 19 percent of total emissions. The Merkel administration predicts that the emissions from cars, ships and aircraft by the end of 2020 will increase by about 2 percent compared to 1990.

https://www.bmu.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Download_PDF/Klimaschutz/klimaschutzbericht_2019_kabinettsfassung_bf.pdf

Difficulties in mobility transformation

Germany boasts Europe’s largest automotive industry with the nation’s prosperity having been built on gasoline and diesel engines. Although German automobile manufacturers are fundamentally in favour of the government’s policies for mobility transformation, it is difficult for them to change their business model in so short a space of time. Electric vehicles (EVs) are recently seen on German roads more often than ever before, but the popularity of fossil fuel cars among citizens still remains as high as ever.

Germany has seen only about 140,000 EVs in use in the first half of 2020. The vast majority of cars, especially those speeding at nearly 200 km/h on the motorways (Autobahn), are gasoline or diesel powered.

This situation has prompted the Merkel administration to significantly expand the number of EV charging stations, with the goal of increasing the number of EVs running on German roads to between 7 and 10 million by 2030. In addition, the economic stimulus package designed to mitigate the negative effects of the recession caused by the Covid-19 crisis includes a supportive measure to offer a subsidy of up to 6,000 euros (720,000 yen at an exchange rate of 120 yen to the euro) to EV purchasers. And yet, it remains to be seen whether it is really possible to expand the use of EVs in such large numbers over the next 10 years.

It is also technically difficult to switch over from the diesel engines of buses, trucks, freighters and other vessels to storage batteries because these modes of transportation require a greater power source even at low speeds due to their large weight, unlike passenger cars. This is why the German government is aiming to decarbonise these vehicles, ships and aircraft by promoting the use of synthetic fuels made from hydrogen.

Remodelling old houses is also essential

The Merkel administration has expressly stated that achieving the target of a 55 percent reduction by 2030 will require a significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from the transport and building sectors.

In Germany, where winters are bitterly cold, improving the efficiency of building heating is critical. The country still uses the buildings (Altbau) constructed prior to World War II after they have been beautifully renovated. Certainly, these old buildings have a quaint, distinctly different feel that cannot be seen in modern structures, but some apartments and offices are not heated efficiently because of their poorly sealed windows and doors. In light of this, the Merkel administration has introduced a policy to encourage people to improve their buildings’ heating efficiency by deducting the cost of renovating windows and other items from their income tax bills.

In addition, the cost of replacing heaters that use fossil fuels such as kerosene with new heating systems powered by renewable energy sources is publicly subsidised by up to 40 percent. Moreover, the Merkel administration has banned the installation of new kerosene-fuelled heating systems from 2026 onwards.

Whether Germans will achieve a 55 percent reduction in their greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 through mobility transformation and the refurbishment of buildings and heating systems will serve as an important milestone in determining if they can attain the goal of net-zero emissions by 2050.

Germany is pushing ahead with one of the world’s most ambitious climate protection policies, and the nation has to navigate a rough road ahead.

R&D Activities in Germany through the eyes of a Germany-based Japanese journalist

In this nine-part series, DWIH Tokyo collaborates with Germany-based journalist Toru Kumagai to bring you the latest R&D trends in Germany.

Click here to read other articles from the series “Toru Kumagai’s report on R&D trends in Germany”.

About Toru Kumagai

About Toru Kumagai

Born in Tokyo in 1959, Kumagai graduated from the Department of Political Science and Economics at Waseda University in 1982 and joined Japan Broadcasting Corporation (NHK), where he gained a wealth of experience in domestic reporting and overseas assignments. After NHK, he has lived and worked as a journalist in Munich, Germany, since 1990. He has published more than 20 books on Germany and Germany-Japan relations, as well as beento numerous media outlets to report on the situation in Germany.